Errors are unavoidable—that sounds unpleasant, but it isn't necessarily so. With good error management, we create a conscious approach to dealing with errors: The particularly nasty ones are prevented, some can be intercepted, and non-critical ones can even be permitted. Allowing errors—that seems risky, especially in a safety-critical environment like medical technology. But if you clarify which types of errors you allow, it's possible to create a safe and fault-tolerant system.

Finding the right treatment for every error situation is what I understand by the term error management.

Error management in the project vs. error management of the product

First, I would like to explain that the term can be used for two fundamentally different areas:

Error management in the projectThis means considering all phases of a project and developing solution strategies for errors that may occur during the project. Project risks, changes due to identified errors, bug tracking, etc. However, I don't want to pursue this topic in this blog post.

Error management of the system: This is about how the product—the medical device or the medical software—handles errors. We want to explore this in more detail and therefore ask...

…what are mistakes?

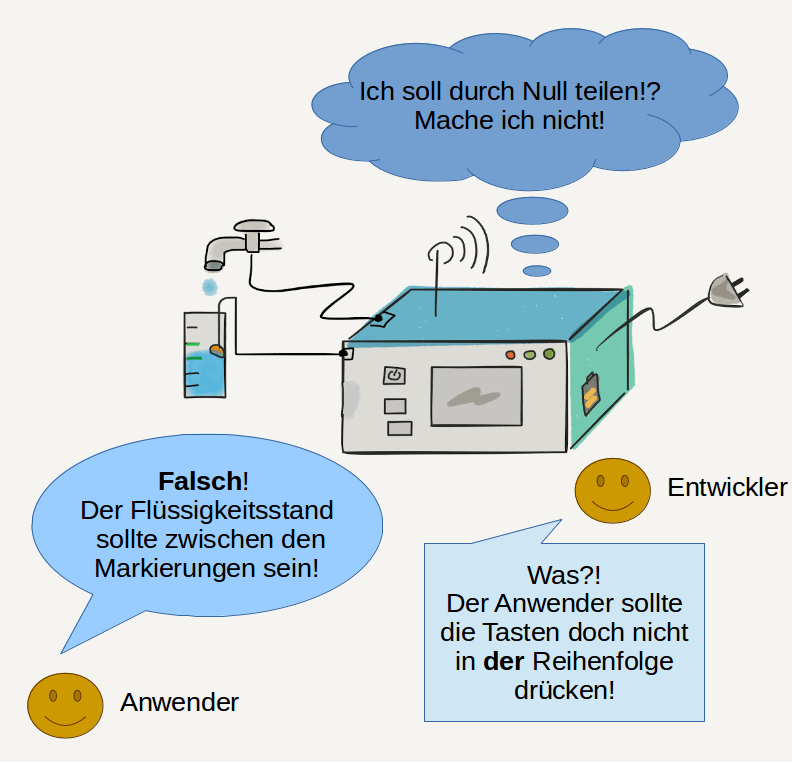

The question sounds simple. But it has many different answers – depending on who you ask:

There are a variety of situations that a user would likely consider errors. For the device in the image above, these could include:

- the battery is almost empty

- and the WLAN partner cannot be reached.

And the inventor (or developer) calls it a mistake if

- the inlet valve is closed or

- the user restarts the measurement until the device overheats.

But the device must be prepared for all these cases. They form the group of Special cases in the error list.

The next worst group are the recognizable errors: Hardware defects and software errors that the device can detect and display, but can no longer handle.

And finally, there are the disasters – Device defects – which are either not recognized by the device or are recognized but can no longer be displayed.

It makes sense to repeatedly refer to this classification of errors and to record the group assignment in an error list.

Get to the mistakes

Right from the start of a project, you should keep an eye on how the system behaves in the event of errors. The foundation for the product's error management must be laid in the first three phases.

Requirements engineering phase

Requirements engineering involves finding out from stakeholders what the system should and should not actually do.

User Stories:

When you spin a few user stories that involve errors, surprising (or even contradictory) things often emerge. And the work has paid off!

Example of user stories related to an error situation:

“The operator wants to be able to detect when a self-test error occurs so that the device can then be repaired.”

“When the device memory is full, old mission data should be deleted to provide the user with at least the data from the current mission.”

"When the device memory is full, logging should be stopped. The user can then decide which old deployment data should be deleted."

The last two stories show that there are different ways to respond to the "storage is full" scenario. And that it's therefore worthwhile to discuss such issues with the relevant stakeholders.

User view of error states:

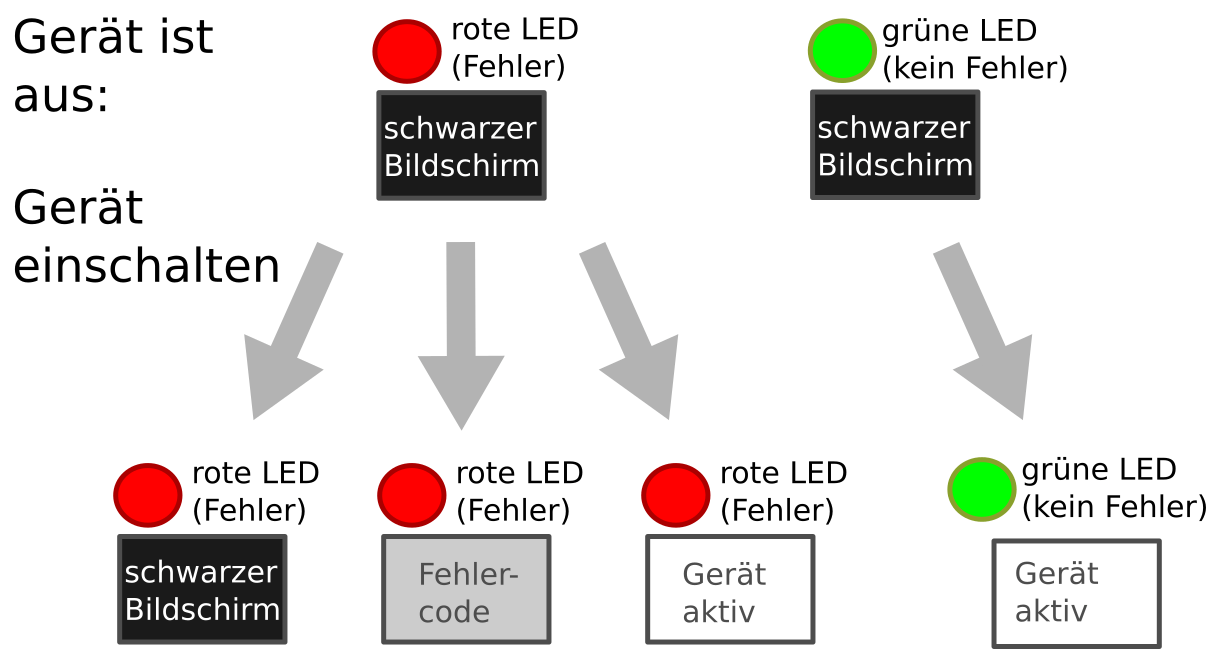

It can be very helpful to draw an image that shows what the user sees in different error situations. Otherwise, it's not clear how an error appears externally. In the following simple example, the device has a red/green LED to indicate whether an error is present.

However, there are errors of varying severity, all of which should result in a red LED. For example, the LED will glow red when the battery is low, when a device self-test fails, or when a fatal hardware defect occurs.

As the image shows, this means that when the device is turned off and the red LED is on, it's impossible to tell what will happen when it's turned on. It might still be functional, it might display an error code, or it might no longer be capable of doing so.

Using such an image, we can work with the customer to ensure that this is the desired device behavior, and there's no need to introduce an intermediate state with a yellow LED indicating a low battery.

Phase: Designing system architecture

The system architecture, i.e. the description of the structure and behavior of a system, should have one (or sometimes several) chapters on the topic of error behavior.

The security concept is the summary of all chapters and sections of the system specification that deal with security—including error handling. Together with the initial risk analysis, this defines how the system handles errors and measures against potential errors.

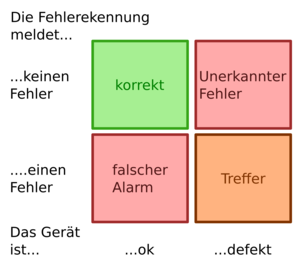

It's important to note that every measure for detecting and handling errors adds complexity to the system and can therefore potentially be a source of errors itself. The following diagram shows the potential effects of error detection:

Each error detection and correction measure considered in the architecture phase must therefore also be assessed with regard to its own error susceptibility in order to decide whether it will be implemented.

In the introduction above, I mentioned that some errors must be tolerated. This becomes clear from this analysis. It's possible that the probability of a particular error occurring and the damage impact are low. However, the associated error detection could be highly susceptible to false alarms. And the error handling could be worse than the impact of the error. In such a case, implementing the measure would be counterproductive.

Example:

A specific hardware defect can cause the system time to be lost. It is possible to provide a circuit that detects this hardware error (error detection) and reports it to the controller, causing the system to display an error screen and prevent further operation (error handling).

However, if this hardware defect and the lost system time do not have any critical consequences – an incorrect time is displayed – and are perhaps even very unlikely, detection and treatment are inappropriate here.

Design phase

The system specification should include a table listing all errors. All of them!? There are a lot!

Yes, all of them! To make this possible, error groups must be defined and summarized. Errors that result in the same system behavior are grouped together. Separate table entries are made for handled exceptions. This table should reflect the classifications listed in the introduction—special case, detectable error, and device defect.

In addition to the error description (short and long) and the device behavior, it is recommended to introduce additional columns. These could, for example, cover the following aspects for each error (each error group):

- Color of the error LED / error code

- the system part / controller that detects the error

- Possibility to troubleshoot

- Classification as permanent / non-permanent defect

As surprising as it may sound, software errors can all be grouped together. Software errors are those errors that don't require their own handling because, by design, they couldn't be foreseen during programming. In good software design, such errors are caught using a uniform method (e.g., asserts).

Unified interception involves less complexity and is often preferable to separate handling, especially when it offers no advantages (e.g., usability). Examples of this (depending on the system) can include corrupted configuration files, lost data packets, invalid file paths, etc.

Example:

On an embedded system, there is a configuration file that must always be present. The user has no control over this. Therefore, it may be legitimate to shut down the system if the file is missing, rather than continuing to run and using a backup file. Because the error indicates a problem: Is the file system corrupted? Or is there a programming error that corrupts the file on February 29th? Creating additional code that only deals with this exception leads to potential further errors.

A few final words

Error management means becoming aware of possible errors and special cases, organizing and classifying them, and handling them according to their impact. For each case, it is clarified how the system remains safe despite the error occurring. For special cases, it is determined how the system remains functional even if it does. Good error management prevents the implementation of unnecessary measures and ensures that usability is improved without unnecessarily increasing system complexity.

Mistake? Smile – you can't kill them all.

Birgit Feld