The term architecture comes from the Latin "architectura," meaning the art of building. When constructing buildings, it has always been common practice to design an architecture. Therefore, everyone has heard of an architect. Few, however, think of an electrical engineer, mechatronics engineer, or software engineer. Especially with complex systems, it is unavoidable to create a system architecture—that is, a blueprint—before starting. Failure to do so usually results in a system that is far too complex and error-prone. The price you pay for foregoing a system architecture can be very high.

The system architect's task is to understand the requirements of a system or product and, from there, design a system that can meet these requirements efficiently, cost-effectively, and reliably. To do this, they have the tools and methods they need to be adept at.

The system architecture is a…

- Tool for designing a system

- Visualization of the system

- Basis for a review

- Development Guide

- Storing information about the system

- Documentation of the system (archiving of knowledge)

- Basis for project planning and cost estimation

- Input for the risk analysis

System context

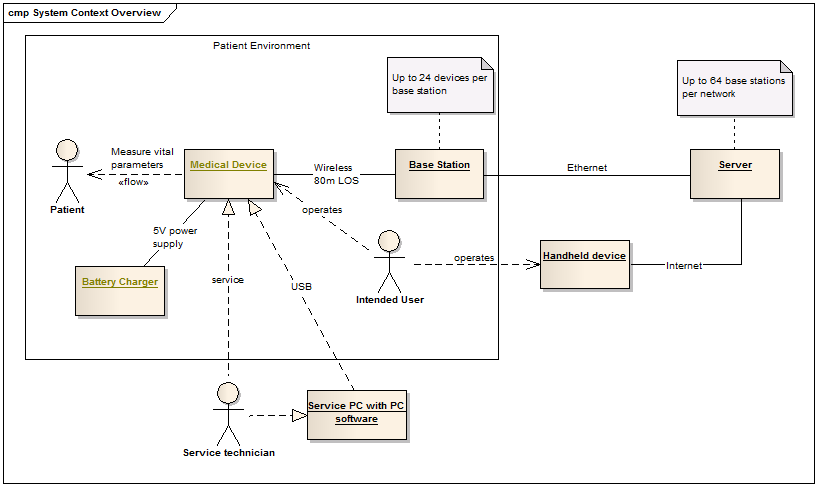

To properly understand a system, it is necessary to know the environment in which it is embedded. A system never exists alone. Therefore, it makes sense to first describe the system context in the system architecture.

The system context includes the people who interact with the device. This could be the user, the patient, the operator, a service technician or the developer. Consider who or what comes into contact with the system and what the use cases are. Ideally, this is already defined in the requirements specification or specifications. Draw these people or systems into the system context. Also depict the application components. These are the interfaces to the patient. Draw in the system boundary and make it clear for which area you are responsible. Name the interfaces the system has and those that arise at the system boundaries. This could be, for example, a user interface or a wireless interface for data transmission.

|

|

| Dipl.-Ing. Goran Madzar, Partner, Senior Systems Engineer E-mail: madzar@medtech-ingenieur.de Phone: +49 9131 691 240 |

|

Do you need support with the development of your medical device? We're happy to help! MEDtech Ingenieur GmbH offers hardware development, software development, systems engineering, mechanical development, and consulting services from a single source. Contact us. |

|

Useful questions to ask yourself are:

- Which people have contact with the system?

- What application parts are there?

- Where is the system boundary?

- Which systems does my system cooperate with and how?

- What interfaces does the system have?

- What use cases are there and does my system cover them?

Be precise with your language and terminology. Create a glossary that covers the terms you need for the system. Discuss the terminology with the client and project stakeholders early on. This will avoid misunderstandings and give everyone a chance to correctly name a component.

Block diagram

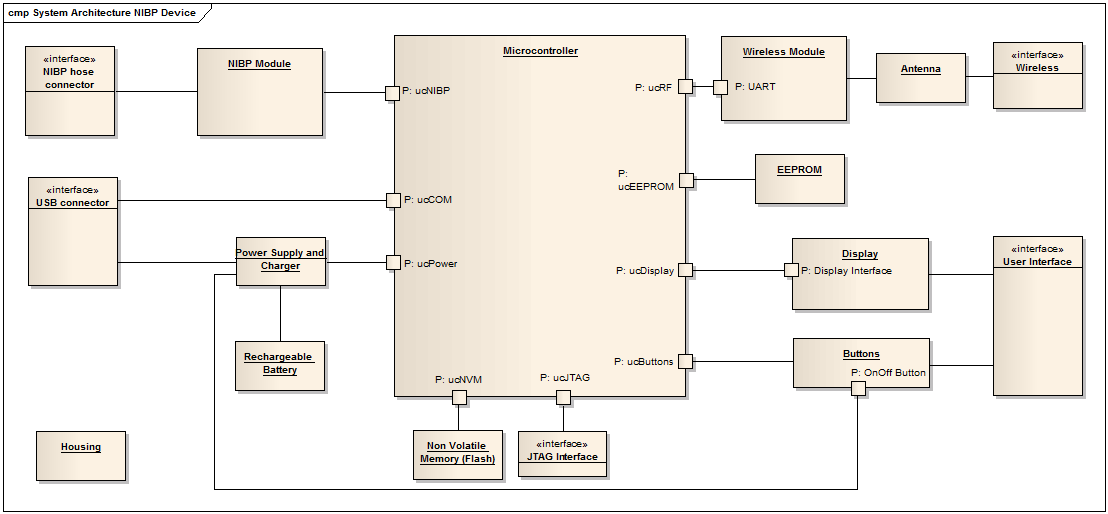

The block diagram is what most people refer to as the system architecture. It is certainly one of the most important parts of the system architecture. A system architecture without a block diagram is like a car without an engine.

The block diagram should contain everything within the system boundary. The system's interfaces should be defined there. The system's components are then broken down and the interfaces between the components are described.

What should you see in the block diagram:

- System boundary

- System interfaces

- Components of the system

- Interfaces between the components

It is important that the block diagram clearly and clearly represents the system's design. It is not necessary to go into too much detail. The details are provided within the framework of the hardware, software, and mechanical design specifications. However, the central components that make up the system should be described.

Check that all interfaces from the system context are mapped. Have you described all components and their interfaces correctly and comprehensively? To do this, mentally rehearse what the device can do (e.g., turning it on, turning it off, recording vital signs and displaying them on the screen, charging the battery, etc.). Consider how the components behave and what is transmitted at the interfaces. This "simulation" takes less than an hour and will help you understand the system and find errors. Go through all use cases.

System behavior

The system behavior is at least as important as the block diagram. Yet it is often forgotten or not created. A system should behave dynamically and not consist solely of static elements. Therefore, the system behavior must be described.

- state machines

- Signal flows or chains of effects in the system

- Error handling

- Response times

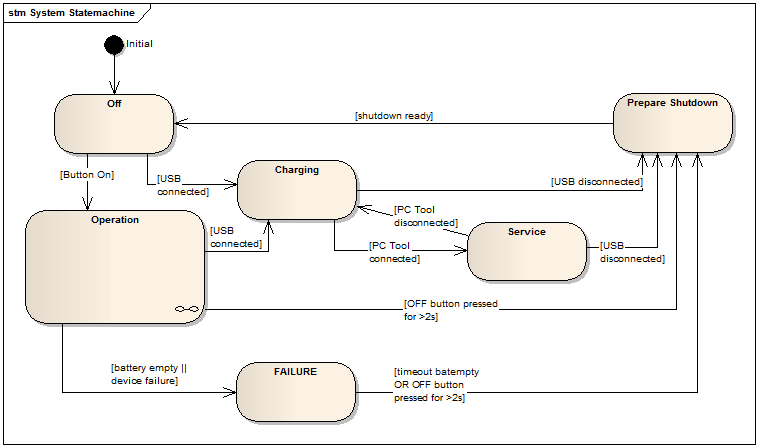

state machine

The state machine describes how the device behaves externally. In the simplest case, it's on or off. But it's usually more complex. State diagrams are the perfect way to represent this behavior. At the end of the day, you should be able to explain the device's behavior using state diagrams. If you can't, then you haven't understood it yourself yet. In that case, it's advisable to invest even more time.

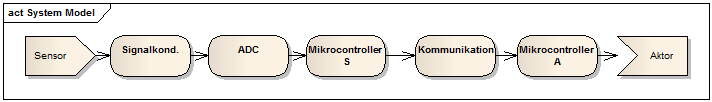

Signal flows or chains of effects

Signal flows or causal chains involve tracking and modeling signals through the system. A signal travels from a source to a sink. It is amplified, filtered, or processed along the way. It is useful to model signal flows to understand the path the signals take and where they ultimately end. The figure below shows a causal chain from a sensor through signal conditioning and an ADC to a microcontroller (sensor). This microcontroller transmits data to another microcontroller, which controls the actuator. This allows you to describe important signal flows or causal chains.

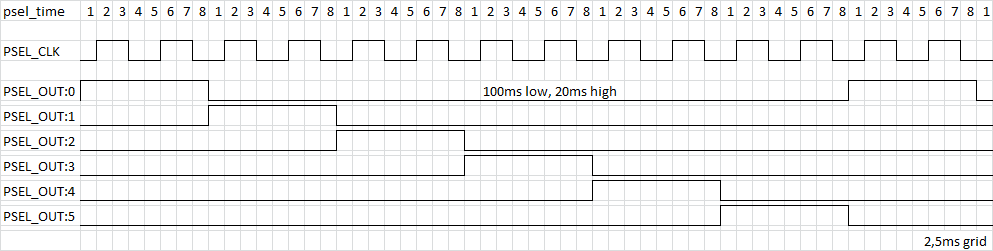

Represent control signals graphically as timing diagrams. Timing diagrams are a very good way to illustrate signal dependencies and greatly simplify implementation. You can also create timing diagrams using Excel if you don't have a dedicated tool.

Error handling

When creating your architecture, consider error management. Consider what errors can occur and how you want to respond to them. Should the device remain usable, or should it enter a safe error state? Create error categories and specify how the errors should be responded to. Model error handling in your state machines.

- What errors are there?

- Into which categories can I group the errors?

- How does the device react to an error or group of errors?

- How is the error displayed on the device?

- What data is stored to help us understand the error?

- How does the system behave in case of an error?

Response times

Reaction times have a significant impact on the system architecture and must therefore be considered. For example, if the system is supposed to respond to a signal in real time, it makes no sense to route the signal through a non-real-time capable operating system. Create a table in which you document the reaction times to an event. Start from an initial state and evaluate an event. Specify a reaction time until the system reaches a target state.

Example:

| Initial state | Event | Target state | Reaction time |

| Device is off | Power button is pressed. | Display shows home screen. | 200 ms |

Alarm concept

A medical device can often also trigger alarms. These alarms can be visual, audible, or distributed. A distinction is made between technical alarms and physiological alarms. Technical alarms indicate something is wrong with the device. Physiological alarms indicate something is wrong with the patient. These alarms are covered in standard 60601-1-8. In the system architecture, you can define how you want to implement the alarm output and whether you need redundant outputs.

Design and mechanical structure

A picture is worth a thousand words. This saying holds true here, too. Often, there is a design draft of what the device should look like (or a previous device). It's much easier to understand a system when you see it. If you have design drafts, incorporate them into the system architecture. These images don't need to correspond exactly to the finished device. The system architecture isn't like a drawing or a design specification. It should reflect how the system is structured and what it looks like in principle.

Include information about what it looks like "under the hood" here. It's important to remember that the system architecture is a living document and that you should update it when components or the device's design change.

If your device has complex wiring or piping, this is the right place to show it.

Power supply

Most systems require power. It doesn't make sense to overload the block diagram with the fact that almost every component in the device requires power. Therefore, it's a good idea to create a separate chapter for this.

In the power supply section, all sources should be specified (e.g., AC power connection, power adapter connection, internal rechargeable batteries or batteries, goldcaps. Don't forget the RTC battery if you have one). The priority of the sources should be defined (the battery is only used when the power adapter is not connected or function xyz is activated). Also define when the battery is charged (e.g., whenever the device is connected to the mains and the battery is < 90% charged).

Next, describe the main consumers (components) and which components are required for switching the power grids. It is not necessary to mention components at the circuit board level. It is important to define how the power supply works in the system and which components are involved. It should also be defined what happens if one of the sources fails (mains failure, battery failure).

Describe how much power the device consumes and what power peaks you expect. Consider the device's runtime when powered by a rechargeable battery or battery. Explain how the device behaves when turned off. Is it truly de-energized, or is a microcontroller running in a power-saving mode somewhere?

You can also outsource this document and reference it.

Description of the software systems

A device usually contains software. This is contained on one or more controllers. It is useful to demonstrate which controllers exist and what tasks they perform. This does not need to be done with requirements at this point; a prose description is sufficient. Furthermore, the safety classification according to IEC 62304 can be performed here. The safety class of the individual software systems is defined. It is advisable to divide the software tasks so that the safety class is as low as possible for microcontrollers with a large amount of code (usually GUIs with operating systems). The safety classification is determined by risk management.

When describing the software systems, it should also be determined which software already exists or will be purchased (SOUP/OTS software). At the system level, this does not concern software libraries, but rather software that is completely adopted (e.g., the firmware in a battery that is not developed in-house). The complete list of SOUP and OTS software must be created elsewhere by the software manager.

At this point, the interfaces should also be named and the protocols between the microcontrollers referenced. The hardware interfaces (UART, SPI, CAN, USB, GPIO, etc.) should be defined, as well as the transfer rates and interface-specific parameters (handshake, 8n1, master-slave, etc.). The protocols define which information is transmitted and in which format. Make sure that all protocols are present.

Operating concept

The operating concept describes the device's user interface in detail. Especially for projects with a large software component, an operating concept clearly reflects how the product should look. The operating concept is created in close collaboration with the product manager. The operating concept should be maintained in a separate document. PowerPoint, Inkscape, or other drawing programs are good choices here. You should incorporate the key elements from the operating concept into the system architecture. What operating elements are there? What displays are there? How is the operation basically implemented? You can reference the operating concept in the system architecture.

What should be considered when designing a system?

Build your systems as simply as possible (KISS = keep it stupid simple). Reduce complexity as much as possible. This requires constantly questioning whether a component is really needed. Figuratively speaking, you need to step back from your drawing board and ask yourself: "Can I simplify something further?" And if the answer is "yes," then keep doing it until you get the answer "no." The effort is worth it, because system complexity leads to excessive testing and unmanageable systems. You can also simplify the system by structuring it better. Assign tasks to the system components and minimize the number of interfaces.

Especially in medical technology, you have to be able to rely on your devices. It doesn't help anyone if the device crashes at the slightest sign of a malfunction and leaves the patient stranded. Therefore, build your systems with fault tolerance in mind. Consider when essential performance characteristics are no longer met, resulting in a device failure. Consider which parts are acceptable for failure and how the other components should react.

Strictly define your system boundaries (what is mine and what isn't?). Fully define the interfaces at the system boundary. Information, energy, or substances can be exchanged via these interfaces. Information comes, for example, from an ECG electrode as voltage or from another device via a USB interface. Energy comes from the outlet or a power supply. Substances could be blood, water, or other substances. Don't forget the mechanical interfaces. For example, a device might have a wall mount or a protective case. Be accurate when describing these interfaces.

Make sure the system is described completely. This is sometimes not so easy, as you have a lot of information in your head. However, this information also belongs in the system architecture. Therefore, question whether the system is described comprehensively without searching for information in your memory. Checking a system for completeness is easiest if the reviewer can read through the system architecture and then explain to the author how the system works. If the reviewer doesn't understand the system and still has questions or can't explain it, then information is missing.

Describe the system completely, but don't go into too much detail. It doesn't matter which voltage regulator the hardware developer wants to use or what the software should look like. That's the domain of the respective experts. You are responsible for describing the system, and you shouldn't unnecessarily restrict the solution space of the domain experts from the hardware, software, and mechanical areas. It's a good idea to review the results of the domain experts to see whether their solutions fit your system.

When designing systems, you should also keep manufacturing costs in mind. It's pointless to design a great system if no one buys it in the end because it's far too expensive. Manufacturing costs are an important aspect that can have a decisive influence on the architecture.

Also make sure the system is manufacturable. This sounds obvious, but it's often overlooked. Discuss your system architecture with manufacturing early on. Initial models (SLS prototypes) can help here.

Consider how the system can be easily tested. It's a good idea to provide interfaces that you need for testing purposes. Ideally, the tests should be automated. Also consider tests that can assist you during development (e.g., an EMC test interface).

Create a safety concept early on. In this document, you document how the system is structured and which safety measures you have defined. The focus here is on safety. For example, you may have dual-channel controls for safety-relevant components. Or you may use redundant hardware to monitor parameters. There may also be mechanical protective measures (pressure relief valve, reverse polarity protection). Here, you also describe the self-tests and device monitoring during runtime and other considerations that contribute to device safety. This document is very useful for discussing the design with the approval authority early in development.

Your contact person: |

|

|---|---|

| Dipl.-Ing. Goran Madzar, Systems Engineer E-mail: madzar@medtech-ingenieur.de Phone: +49 9131 691 240 |

|

Do you need support with the development of your medical device? We're happy to help! MEDtech-Ingenieur offers hardware and software development, systems engineering, and consulting from a single source. Get in touch. |

|

You don't have to reinvent the wheel with every project. Look for components that you can reuse. This saves development effort and can also have a positive impact on manufacturing costs. When building your system, also try to consider whether reusable modules can be created.

Pay attention to hidden dependencies in a system. These are not easy to detect (Example 1: Volume depends on the battery level – a low battery is signaled by an acoustic alarm; Example 2: Charging the HV capacitor of a defibrillator during mains operation causes a disturbance in the ECG, which leads to the heart rhythm being classified incorrectly). Go through the system in a structured manner, looking for such hidden dependencies. To do this, you can create a list of application scenarios and, for each scenario, evaluate which other scenarios in the list it might affect. This creates a matrix of dependencies. Errors resulting from these are very difficult to detect and only come to light very late in development.

Consider whether the system fulfills the customer benefit. Customer benefit is the reason why a customer buys the system. Are the use cases plausible with the created architecture? Make sure that users can use the device to do what you are developing it for. If the customer benefit isn't yet clear to you, then there's no point in venturing into the architecture. In that case, I recommend you think about the customer benefit.

Conduct early reviews of the system architecture. Have colleagues review parts of the architecture during development to improve it early on. It's easier for a reviewer to read through a few pages than the entire architecture at once.

I hope this article has given you some food for thought. Designing systems is fun! This topic isn't about a tedious document, but rather a tool that helps you develop systems efficiently and professionally. I welcome feedback and would love for you to contact me. Feel free to leave a comment on this article. If you know someone who might also be interested in this blog, I would be very happy if you would recommend it to others.

Best regards

Goran Madzar